During the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain, factories were plagued by dangerous, unsanitary, and inhumane working conditions. In the late 19th century, the Matchmakers’ Union—the first trade union for British women in the match industry—emerged to fight for a decent working environment. By actively supporting strikes and boycotts, it became a symbol of protest against industrial exploitation. Read more on londonka.

The Founding and History of the Matchmakers’ Union

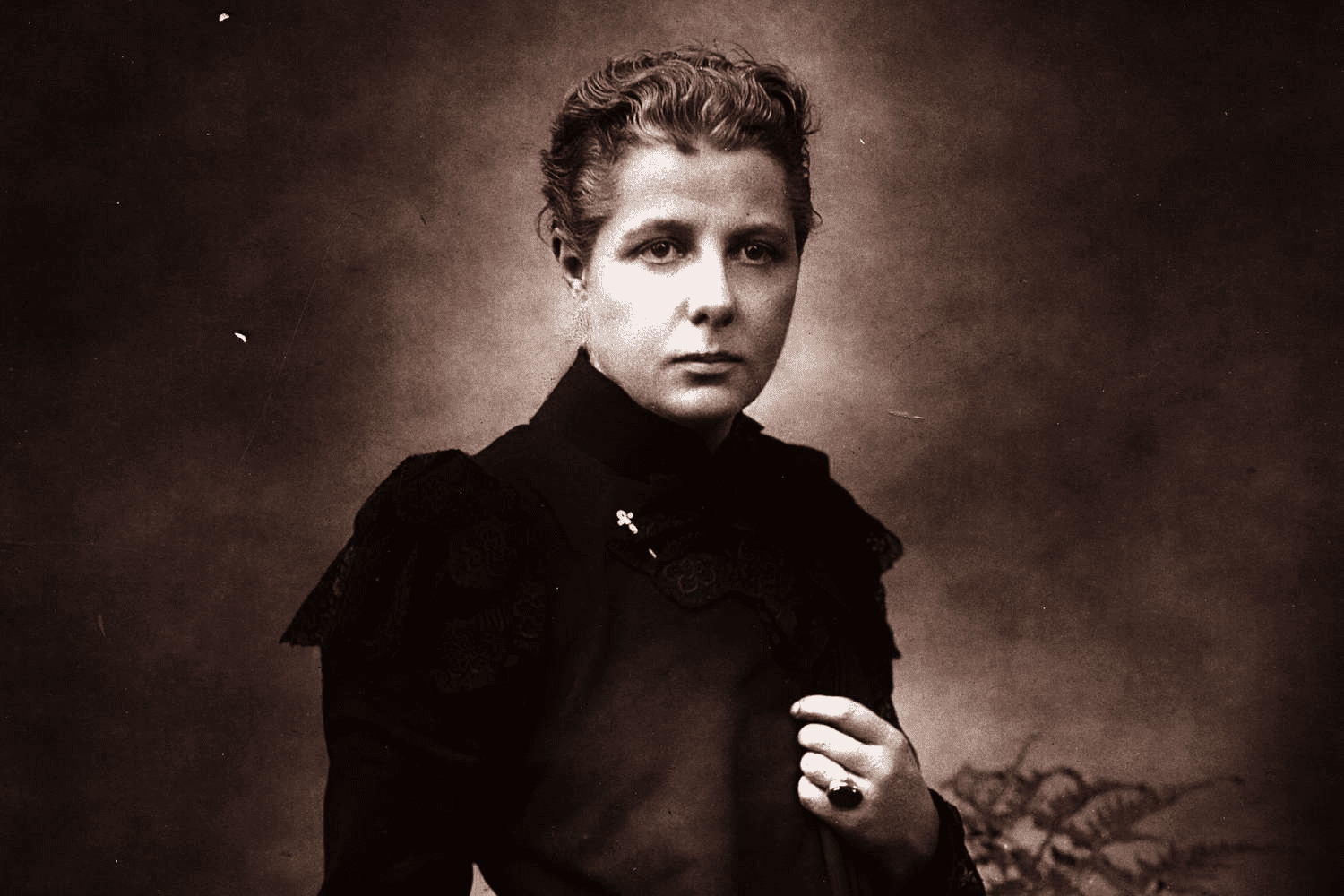

In June 1888, the English activist Clementina Black raised the issue of female labour at a meeting of the Fabian Society. Her contemporary Annie Besant was in the audience and was shocked by what she heard about the conditions for workers at the Bryant & May match factory. Deciding to conduct her own investigation, she uncovered numerous abuses. Women were forced to work up to 14 hours a day, earning less than five shillings a week. They often lost a significant portion of their wages to fines, which were imposed for talking, dropping matches, or visiting the toilet without permission. Furthermore, the activist discovered that working with white phosphorus was causing serious illnesses among the women.

Soon after, Annie Besant wrote an article in her newspaper, The Link, titled “White Slavery in London,” criticising the working conditions for women at the Bryant & May factory. In response, the company tried to force the workers to sign statements declaring their satisfaction with their jobs, but some refused. When these women were dismissed, over 1,400 of their colleagues walked out on strike. Through their publications, Annie Besant, William Stead, and Henry Hyde Champion actively called for a boycott and raised public awareness of the situation. For her part, Besant agreed to become the leader of the future Matchmakers’ Union.

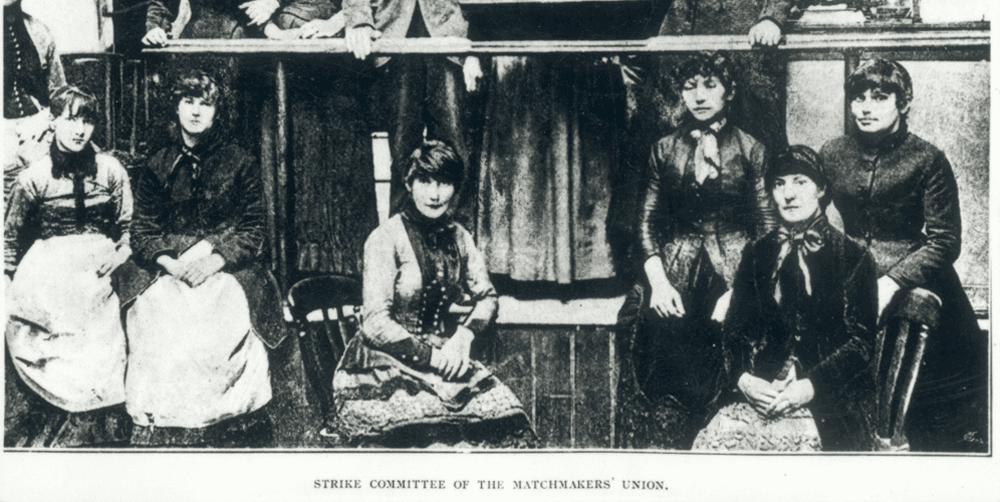

On 27 July 1888, the first meeting of the trade union was held, chaired by Ben Cooper, the secretary of the Cigarmakers’ Trade Union. A general committee of 12 women was elected, with strike organiser Sarah Chapman as president, Annie Besant as secretary, and Herbert Burrows as treasurer. In addition, an advisory committee was formed that workers could turn to for help. Thanks to money saved from the strike fund and a charity event, the members were able to secure a permanent office.

Shortly afterwards, the Bryant & May factory announced it was prepared to re-hire the dismissed women and abolish the system of fines. Having agreed to the terms, the women returned to work in triumph. At the same time, by being open to both women and men, the Matchmakers’ Union attracted over 650 members by October of that year. The union continued its campaign against the use of white phosphorus. In 1896, it took part in the International Socialist Workers and Trade Union Congress in London. Members presented a resolution calling on workers in all countries to pressure their governments to ban the use of white phosphorus in match production. Following a reputational crisis, Bryant & May’s director, Gilbert Bartholomew, announced in 1901 that the company would stop using the poisonous substance. The Matchmakers’ Union was dissolved in 1903.

ThoughtCo, Annie Besant

The Legacy and Impact of the Matchmakers’ Union

The Matchmakers’ Union demonstrated the effectiveness of organised struggle in the fight for workers’ rights. It played a crucial role in improving working conditions and drawing public attention to the problem of hazardous materials in the workplace. As a vital step in the development of the women’s labour movement, the organisation served as an inspiration for the future protection of exploited and low-paid employees.

Wikipedia